Why our startup failed

One would never expect their startup to fail 6 months after having raised half a million euros from public investors. It eventually happened to me, as the CTO of Dijiwan, a former digital marketing startup based in Bordeaux, France.

§tl;dr

A good product idea and a strong technical team are not a guarantee of a sustainable business.

One should not ignore the business process and issues of a company because it is not their job. It can eventually deprive them from any future in that company.

§Why writing about it only now?

Success and failure are bound to Time.

And Time flows differently whereas you are in a rising or an abyssal phase.

- We initiated the Dijiwan project around September 2010;

- We initiated the Dijiwan startup around September 2011;

- Dijiwan raised 0.5M€ in January 2012 from French public investors to develop its business within a year;

- Dijiwan started struggling to clear its paychecks in July 2012;

- Dijiwan requested bankruptcy protection in September 2012.

Why write this side of the story a year after the bankruptcy? Why not sooner?

Now is a good moment.

Prior to now, I would have put too much emotion into the analysis. It could have been perceived as some sort of revenge or an easy backstab of a rotting corpse.

One sometimes needs time to step back and to acknowledge one’s own failures.

§Trust your gut feeling

I remember my first conversation with the CEO of the company: it went directly to the bin of my memory. Too many buzzwords. Too much flattery. So nothing much, really.

I learned about that the second time we met, as I did not recognise him while he did recognise me.

The dating continued a couple of times more: I was definitely attracted by the innovation of the product (mining and mapping networks of Web content).

I was not convinced by the CEO… but well, as the idea was to raise money first, I decided to ignore my gut feeling and to aim for the success of this operation.

Raising the money equaled building a dream team in ideal conditions. I could not believe it could not work. So I purposely ignored my initial judgement.

§Terrible hiring and management

Each hire should be tight to objectives, costs and metrics.

- Is the hire generating revenues, is it creating product value or is it sustaining the organisational growth?

- How do I know if the job is properly done?

- Have we agreed on the contract termination conditions?

- Is the hire the result of an internal inefficiency or is it required due to work overload?

We had 2 marketing officers, 2 business developers, 2 strategy analysts, 1 researcher contractor and 4 developers when operating at full speed.

If we analyse the figures:

- 2 people had the responsibility to bring money on board;

- 2 people had the responsibility to broaden our visibility;

- 3 people had the responsibility to deliver customer studies and analysis (1 analyst + 1 researcher);

- 5 people had the responsibility to build the innovation (4 devs and 1 researcher).

In addition to the previous numbers, we fired 2 marketing officer, 1 developer and 2 design contractors.

This is both too much and not enough at the same time:

- we signed less than 100K€ of contracts with 3 or 4 customers;

- we had too many people to produce customers’ deliverables;

- the high marketing turnovers reveals a large bottleneck and inefficiencies.

One of the failures was clearly the will to spend all the money rather than to spend it wisely. The primary objective should have been to generate more revenues or to sustain the innovation — if it broadens the business reach and simplifies customers acquisition.

§Reckless expenses

Around 600K€ were burnt in 6 months if you consider the revenues and the funding. For a 10 people company, this is a lot!

Barcelona’s Mobile World Congress 2012:

- I remember seing nice pictures of nice cocktails and nice restaurants from the business developers;

- I remember seing lots of appointments with potential customers;

- I remember it ended up with no customer but a partnership;

- I still do not know the cost of the operation, even as a cofounder.

A customer trip’s cost to visit Lisbon:

- 6 people trip with paid hotel and so on;

- 1 person speaking to showcase our work and our product;

- The goal was to sign new contracts with other affiliates of the group;

- No contract has been signed therefore;

- Again, the cost of the operation has never been communicated.

I never had access to the accountancy results. It bothered me but I did nothing because I never thought it could possibly be that bad, that fast.

The cherry on top: we received a massive LED TV screen to demo the product to customers in the same month the first paycheck was rejected.

§Unbalanced partnerships/contracts ratio

A fresh and innovative company can struggle to convince people to pay for their service even though they have no public credibility yet.

We granted a lot of discounts to get customers on board. For the sake of signing new and more cyclic contracts afterwards. The contracts never happened.

We most often ended up accepting a partnership. Which means producing a free work as a proof of concept that our product worked for the customers. It was associated to a shallow promise to sign regular and paid contract afterwards.

It never went further the free work as a lot of excuses suddenly appeared: we will see later, our marketing manager got a promotion etc.

Providing free work has a cost.

A 2 week free work effort costs a month of salary of every person working in the company. So it is certainly not free.

Waiting for customers, waiting for customers to make a decision, hoping a customer will say yes, waiting for the customer to sign the check after saying yes is a very long process.

During this time, your company has to pay for expenses, costs and salaries.

Work is not free. Not signing a single paid contract is called bleeding to death. And this death is a slow process.

§Big customers = lots of time

Speaking of customers, the main lesson here: the bigger the customer is, the longer the process is.

A small company has time to choke several times during a single big company heartbeat. A small company has time to die several times during a single contract decision process of a big company.

The promise is the following: a startup thinks it has an innovative solution. A startup thinks many other companies would pay for it.

However these companies made their life without you, most probably for years. In the end, they do not care much about you. They will listen to you. It will be entertaining. It will create hope. But they want to make sure you will exist in a year or two, at least.

They will most likely not eat out of your hand if they can perceive you need them at first. It is like a hobo trying to date the Prime Minister because he found the secret of political success. Even if the promise is beautiful, it will not happen. Never.

An innovative company needs to convince first. It needs to showcase its product, to demonstrate its benefits and the value added to any customer willing to pay for it.

In order to summarise the startup paradox:

- a startup does not have time and needs money to survive;

- your potential customers have the money and need time to see if you will survive;

- the money you do not have yet is money you do not have at all.

Dijiwan announced its 1M€ contracts objective for December 2012 whereas it actually signed contracts for less than 100K€ in total (article in French). It was in May 2012. The first choke happened only 2 months after.

The bigger the lie is, the more inclined to believe it you will be. Except your potential customers. They will wait. Their timescale is not your timescale.

§The CEO bottleneck

Our CEO had charisma. A lot of charisma.

I reckon if I did not trust him at first, I trusted he could manage to get the business to rise and to shine. As his words were strong and beautiful, I ended up trusting him.

Trusting is accepting. Successes and mistakes. And one needs time to acknowledge their trust to be a mistake.

A lot of decisions appeared to be wrong in the end, mostly thanks and because to his charisma and its relationship with our weaknesses:

- the hires depended on him (except for the tech team);

- the contractors depended on him (even if no one agreed);

- the accountancy depended on him;

- the business depended on him;

- the product development did not depend on him.

Can you see the bottleneck here?

The decision process was top to bottom by authority. The only area out of his scope was the innovation and the technical team.

The CEO of the company did eventually know how to manage a company like a boss. But he did not know about his own product. Therefore he was neither convincing nor able to sell it. He was selling carpets rather than the crafted outcome of his soul.

Because of that disconnect.

A startup does not need a CEO. A startup does need a steward.

A startup does truly need a leader rather than a director.

A startup does need champions first.

This is the credibility of the company: its people, their individuality and their experiences.

§Ignoring problems

I mainly ignored problems because I never thought how bad it could end up with. I thought we would shut down the company if we had no more money to pay ourselves. I thought we would know if we did not have money anymore.

Many symptoms accumulated along the weeks:

- no contracts signed despite the numerous business trips to Paris;

- endless negotiations with big customers;

- endless negotiations for a next funding round with private investors;

- 6 months for the marketing team to produce a 6 pages website;

- no follow up from hot customers from a month to another one;

- more and more promises during our monthly board meetings;

- extreme difficulty to find out precise and quoted details about expenses, accountancy and so on.

The tension between us (the cofounders) eventually arose and grew. I paid less attention to ours conflicts because I felt it was useless to waste energy.

I rather preferred to focus more on the doing part of the product, to care even more of the people. Not to buy a conscience, but because I felt wasting energy in verbose and sterile conflicts would be no help.

Later is not an answer. Promising millions is never an answer either. Neither is ignoring the problems, and thus my responsibilities.

§You need to add value, not complexity

I thought the product we made was worth it for the customers we were targeting: marketing companies, companies in a need for an online strategy and companies in a need of improving/measuring their online strategy.

We created the company on top of an existing proof of concept of online data mapping, entirely manual, long and error prone.

As the idea was to automate and hasten that process, I never asked myself the question if it was that the customers needed.

I think we had too much hesitation in the decisions about what we were able to do and on the delivered product as well.

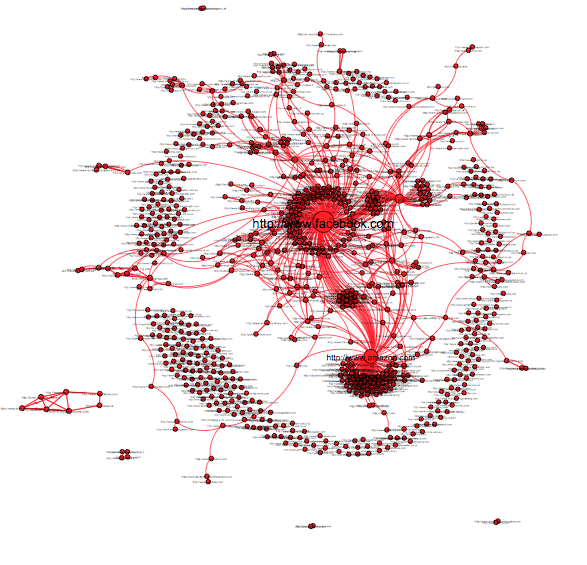

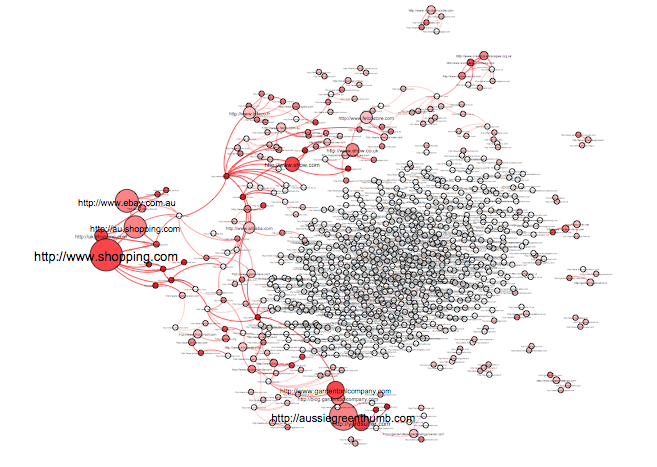

I mean, who in the marketing industry is able to decode a 15K€ Web graph even if it contains loads of useful informations? And that was our number #1 feature.

Now, I acknowledge the graph data was essential. We should have delivered them in an more effective and practical way: spreadsheets, data views (who are the influencers, how can I contact the websites owners, recommended keywords for Facebook/Twitter/newsletters per group of users etc.).

We should have sold a set of of lists with pictures, a few simplified maps and targeted howtos rather than an army-grade Web satellite radar with full control in your hands.

The learning curve of providing useful and high value data is rather low compared to putting all the informations in a powerful and new, and thus complicated tool.

Most of all: it would have been easier to understand. Thus to sell, to grow and to convince. And for us to survive.

We built a nice piece of software. But we never acquired any additional customers by polishing a line of code or by adding a new feature. Because those lines of code never faced anyone willing to sign a check.

§You do not need money

A private investor once said to us:

I want to make sure you do not need my money.

It might be strange coming from an investor but I reckon it is a smart advice. Investors should either help in either ways:

- idea bootstrapping through a cheap prototype to test a market;

- prototype iterations to test even more a market;

- business growth based on a proven (yet successful prototyped) idea.

No one will blindly throw a million or two in your company because you have a cool idea. It will happen only if you have a good and proven track record, a renown team, a low risk/high return on investment business or a high risk/flourishing activity.

At the time, we needed money to survive. I did not know it. But that was the case. The investors wanted to see if our idea and working MVP was capable of succeeding in the real world. The world where other companies buy your product.

Also, customers will not sign a check to a person they do not trust. I discovered that way too late, when the company collapsed: former prospects acknowledged they did not trust our CEO, even if they loved our idea and product. They smelled something wrong.

Damn you bottleneck!

§Pulling the fire alarm

When do you need to pull the fire alarm?

What to do if the company goes down into madness?

Surprisingly, a company officially goes wrong only when it can be proven. Which in financial words means: when a company has debts.

As a cofounder, I should have acted quicker. As soon as the first employee notified us about his rejected check. As a bank never blocks an account straight off, you can imagine it has been going on for a while.

What could I have done? Ask the CEO to leave? My only evidence is that we had run out of money. I still wonder if debunking a problem from the inside is doable on your own, without the consent of a majority.

Instead of acting, we had continued trusting the CEO despire a lot of suspicion. A very largely tainted trust I admit.

We eventually waited 2 months before declaring unpaid salaries to the Chamber of Commerce and to the local Job Office.

We got a little help from trade unions, and mostly figured out how complicated our situation was: a locked cage above a precipice.

When the CEO learned about our action, he anticipated the move smartly: the Chamber of Commerce canceled our audience because… the CEO has requested this very same Chamber’s protection!

A way to hold bankruptcy by freezing the debts while staying on board. At the time, the ambiance in the office was nasty and no one had any motivation neither trust regarding the CEO.

We had to push hard to get fired. Yep, because everybody wanted to leave. By being fired, people could at least sustain temporarily on government benefits.

When you have a continuing contract in France, you are bound to it. If you want to break it, you can. However you will not get any government benefits while you search for a new job; even if it is due to a lack of responsibility of the employer.

If you want your money back? You need to hire a lawyer to go to a special court. Which means committing money to get your money back. A year later.

This is that long of a timescale.

§Where are the public investors?

We also pulled the fire alarm with our public investors. We had an emergency meeting. A meeting where the CEO promised 3M€ of potential contracts. I can still giggle nervously when I think about it.

We had to send them a report. It was sent. Thus I do not know about its content as at that time, I was already pulled off the communication channels.

Since then? Well, not much. Apparently saving a half million of public investment is not worth it. Not we were requesting money, but just help. To clean up the mess and to heal the pain.

I have not been aware of any feedback after we got the money from funding. To verify everything was okay or even to connect us to other useful persons to fuel the growth.

NO-THING.

They only cared about us creating jobs in the region. When it was about unpaid employees suffering they did not give a shit. And for that, I am still very angry about this irresponsible behaviour.

This experience gave me a dirty after taste of how money can be more destructive than constructive.

§Conclusion

Some of the mentioned problems are not a potential sign of death on their own. You can ignore problems for sure. You can escape from your responsibilities for sure. But the job needs to be done.

If the job is not done, that is the problem. Period.

I now think ignoring that problem is a fatal mistake.

And we paid the price for it.

Startups are not bad. Public investment is not bad. Slow justice is not bad either.

What is wrong is how freaking difficult it is to extract yourself from this mud, willing and helping your pairs not to drawn in something you created.

What is wrong is that fucked up money thing to make more money for the sake of making more money. Or to ignore the loss of half a million because you know, it is better that a local innovative company dies rather than acknowledging it should have required a little care.

If I had to do it again? I would do it again, differently. Without the scale in mind. Without the wrong people. For a right balance.